In Defence of Interesting Times 10.07.17

In the second in a series of Planet Extra articles giving in-depth reflections on the 2017

General Election from different perspectives, Daniel Gerke celebrates Jeremy Corbyn’s success,

and examines its implications for Wales. He analyses whether the election marks

the welcome end of neoliberal orthodoxy in the Labour Party, but cautions that

all is not roses and Glastonbury appearances…

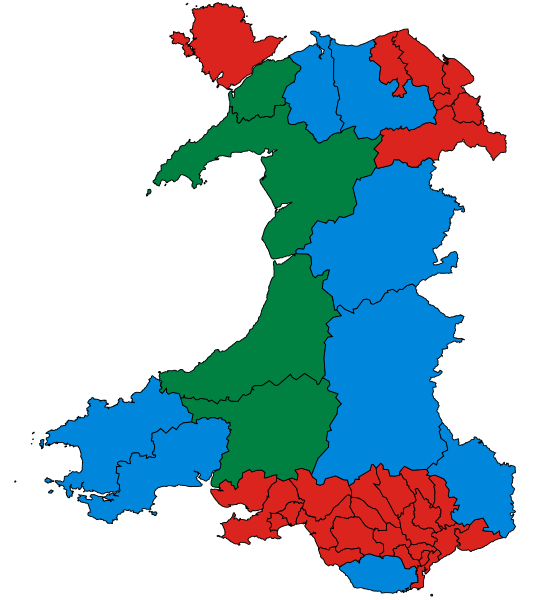

Wales Parliamentary Constituency 2017 Results © Brythones.

The apocryphal Chinese saying ‘may you live in interesting times’ is generally invoked as a curse; it expresses a spiteful, conservative desire that an enemy languish in what the Italian Marxist Gramsci called an ‘interregnum’, a period of stark uncertainty in which ‘a great variety of morbid symptoms appear’. Today, I think we can afford to redeploy the term in a spirit of optimism. As I write, Jeremy Corbyn is the unassailable leader of the Labour Party and is on track to win the next general election, whenever that may be. On June 8th, Corbyn led the party to gain thirty seats, mainly from the Tories, devouring Theresa May’s majority and all but guaranteeing a much softer Brexit than we would otherwise have had to endure. Corbyn’s approval ratings now soar above May’s and, in the only available post-election poll, Labour have a 6% lead, enough for a majority. We do indeed live in interesting times, and thank goodness we do. Predictability was killing us

How things have changed. Rewind to 1982 and Tony Benn, Dennis Skinner and a handful of other left-wing members of the Parliamentary Labour Party were forming the Socialist Campaign Group (SCG) as a bastion of socialist values and policy in a party increasingly managed from the centre. Throughout the neoliberal era the SCG members, including Corbyn, Diane Abbott and John McDonnell, consistently opposed the onslaught of reactionary politics that was launched in earnest within the Labour Party with Thatcher’s first victory in 1979. As neoliberalism was deemed, increasingly, the only game in town, the process of change within the Labour Party, along with its right-wing trajectory, appeared irreversible. Over the course of three general elections between 1983 and 1997, a coalition of centrist liberals and disillusioned socialists transformed Labour from a moderate social-democratic party to a vehicle for what the political theorist Nancy Fraser terms ‘progressive neoliberalism’: Thatcherite privatisations, union-bashing and financialisation combined with social justice for women, minorities and LGBT+ people. The latter development was of course very welcome, but the failure of New Labour to challenge Thatcherite orthodoxy was unforgiveable (not for nothing did Thatcher call Blair her ‘greatest success’). It is no exaggeration to say that by the time Tony Blair arrived on the scene, the SCG were a democratic socialist fragment within the body politic of a liberal party.

What we have following the general election of June 8th, 2017 are Blairite and Brownite factions of rapidly diminishing influence within the body politic of a democratic socialist party. They will be welcomed into the fold by those of us who backed Jeremy Corbyn from the start, but they will not be allowed within a hundred miles of the levers of power. There will no repeat of the disastrous ‘chicken coup’ of mid-2016, in which Labour were tanked in the polls by the most futile leadership challenge in history; the kernel of Owen Smith’s doomed offering to the Labour selectorate was, in effect, ‘I’m not Jeremy Corbyn’: the exact opposite of what they wanted to hear.

It turns out that ‘I’m not Jeremy Corbyn’ doesn’t wash with the wider British public, either. The shameful collaboration between the Labour Right and the reactionary press, the unrelenting smear-fest, was largely met with a shrug from the British people; strangely, working people would actually quite like free school meals and a £10 minimum wage. ‘Oh, Jeremy Corbyn!’ sang a stadium full of young people to the tune of The White Stripes’ ‘Seven Nation Army’, before going out and voting for him. Neoliberal orthodoxies about the feckless, apolitical young be damned. The times they are a changin’. Jeremy Corbyn is dragging Labour kicking and screaming back to its roots in social democratic universalism, egalitarianism and class analysis, while retaining and indeed broadening the social justice agenda; a Labour government would, for example, ‘gender audit’ all legislation for its impact on women, formalise the rights of disabled people in law and enforce LGBT+ inclusivity in sex and relationships education. A Labour majority government committed to the party’s current platform would, in my opinion, be the third truly transformational government since the war (after Attlee and Thatcher).

Jeremy Corbyn graffiti by She She Gabor + Candie © Duncan C http://bit.ly/2tzUt9u

All is not roses and Glastonbury appearances, however. For those of us with a traditionally Marxist orientation, Labour’s current class-oriented universalism is a welcome antidote to the means-testing, British post-imperial jingoism and dishonest triangulation of the Blair era. Gone are the days of having to reconcile appeals to the self-interest of tortured electoral coalitions, followed by the inevitable policy fudge. Labour under Corbyn has become confident in asserting consistently socialist-universalist justifications for policy choices. At the same time, however, the strategic and moral value of regional particularisms and the impulse towards self-determination, recognised by Marxists of such stature as Raymond Williams, risks being underestimated by the newly ascendant ‘Westminster Left’. The weakest link in the chain of the Labour movement is no longer its neoliberal sycophantism, but its failure to see that in the long term, a progressive alliance is the only way to break the iron grip of the Tory Party.

The Greens in particular, but also the Liberal Democrats and Plaid Cymru, made practical advances towards a logic of alliance this summer, and were generally rebuffed by a persistent strain of regressive tribalism within Labour. Clive Lewis, the most vociferous champion of cross-party collaboration on the Labour Left, remains marginalised, and I am dismayed to see him absent from Corbyn’s loyalist dominated post-election reshuffle. Scottish Labour, I am reliably informed, campaigned not against the Tories but against the SNP, in some cases actively encouraging a Tory vote to unseat a nationalist. This is, frankly, a disgrace. Unless real electoral concessions are made to nationalist voters in Scotland and Wales, and a true popular front mentality is engendered within the party as a whole, Labour will find it difficult to consistently win parliamentary majorities, which is what it will need to do in order to fully implement its visionary programme. Towards this purpose, the democratisation of the Labour Party must continue apace, since at the grassroots level, away from the aggressive ‘factioneering’ of Westminster politics, the progressive alliance is already in part a reality.

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

About the author

Daniel Gerke is a PhD candidate at Swansea University, studying the influence of Western Marxist thinkers on the Welsh cultural critic and novelist Raymond Williams. He writes on politics, Marxism, psychoanalysis and literary and philosophical realism.

If you liked this you may also like:

A Welcome out of the Darkness: Rebuilding Common Values after Brexit

Counsel General for Wales Mick Antoniw AM draws on his experience of growing up in the Ukrainian refugee émigré community, and his work as a member of the EU Committee of the Regions, to explore how Wales could retain connections with Europe, and sustain common values of solidarity, peace and equality.

Plaid Cymru: An Alternative to Punch and Judy Politics

Sioned Williams draws on her experience of campaigning for Plaid Cymru. She details the challenges faced by Plaid in June, due to the assertion of an increasingly ‘gladiatorial’ two-party politics, and the alternative Plaid offers should Labour fail to stand up for the Welsh economy as the UK leaves the EU.

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…