Gwales 2007

(...a personal perspective...) 15.08.13

The poet Iwan Llwyd gives his thoughts on the National Eisteddfod and its interaction with the outside world.

There’s something about islands that has always gripped and fired the imagination. I’m writing this piece while on holiday on the island of Cyprus, once one of the richest islands in the Mediterranean, but now deeply divided by race, history and religion. The same can be said about Ireland, Sri Lanka, Fiji and even New Zealand (all surprisingly enough, once colonised by the British).

Islands can also be strongholds — as Ynys Môn or Anglesey once was for the Druids in the face of the Roman legions, and as was Malta in more recent times. Islands have a special place in our native legends. In the Mabinogi, Britain was the ‘Island of the Mighty’, and in the second Branch, telling the saga of Bendigeidfran and Branwen, Efnisien and Matholwch, the warriors of the Island of the Mighty had to go to war with the Irish over the honour of Branwen, King Brân’s sister, who had been humiliated by her new husband, Matholwch, the king of Ireland.

As in all the branches of the Mabinogi many intricate strands are woven into the story of Branwen, but the legend reaches a climax in a fierce battle between the British and the Irish, with the Irish having the advantage of the Pair Dadeni (The Cauldron of Rebirth), where every dead warrior thrown into the cauldron would re-emerge a fully armed fighter, but unable to speak. Ironically the cauldron was Brân’s wedding gift to Matholwch on his sister’s wedding. Welsh fortunes were bleak indeed, until Efnisien, Branwen’s half-brother, the instigator of all the troubles, threw himself into the cauldron and burst it into smithereens. As the story recalls, this was a kind of victory for the Welsh, but not much of a victory, as only seven warriors returned to Wales, with Branwen, and the head of her brother, Brân.

Branwen died of a broken heart, on the island of Anglesey. The others followed the ‘head’s’ instructions and journeyed to the island of Gwales, off the Pembrokeshire coast, who many now think to be Grassholm, a paradise for sea-birds. There the seven were entertained for eighty years, without a care in the world. Bendigeidfran’s head recounted the innumerable exploits of such heroes as himself and Pryderi and Pwyll, while the birds of Rhiannon created the most amazing music. And in their post-traumatic stress after the horrors of Ireland the seven forgot everything about that terrible war.

After eighty years of this reverie, one of the seven, Heilyn ap Gwyn, asked himself what was beyond the door at the end of the room, the door toward Aber Henfelen in Cornwall. The door they had been told never to open. And his inquisitiveness, and probably boredom, got the better of him, and he stepped forward and opened the door. And all the woes and grief and horrors of the past came and flooded the room, and they had no choice but to leave Gwales and follow Brân’s instructions and bury his head in the White Tower in London — where ravens still keep watch.

I can’t help feeling that the National Eisteddfod is our own contemporary Gwales. The elements are all there. The escape from the grind and the greasiness of twenty-first-century culture and society. The opportunity of being with people of a like mind and experience. Almost a totally Welsh-speaking experience, encompassing music, poetry, comedy and camaraderie. The seven veterans from Ireland would have been well at home.The guy on the PA was the ‘master of ceremonies’.

‘When I mixed for the Talking Heads back in 1987, I had to tell them the bass amp should be aligned behind the bass drum. They could have put some blacks behind this stage! And look at the lighting. My grandfather from Pontrhydyfen was the first person ever to run a sound system at the Eisteddfod. He lives in Chester now. Still ‘as the accent though.’

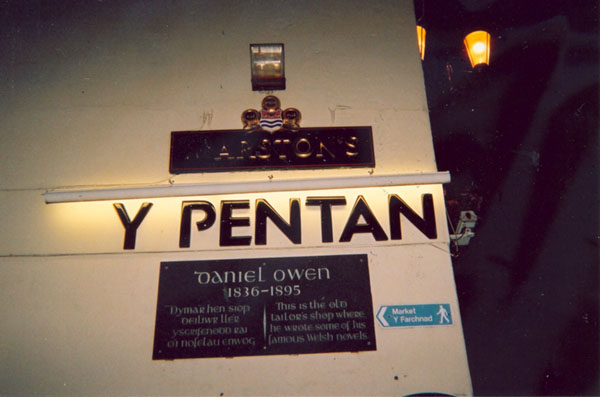

As people sip lager from plastic glasses, this is typical of the conversations all over the Maes, let alone in the fringe and evening events, during the Eisteddfod, in both languages. This year Wales’s premier culturefest was held in Mold, within a few miles of the border, and fast becoming part of Chester’s hinterland. Indeed, many prominent Eisteddfodees were staying in Chester because of a dearth of suitable accommodation closer to the festival. But they were staying on the Welsh side of the river Dee, they insisted.

Until a few days before the official opening there was considerable doubt whether it could be held at all. The torrential rains of June and July had turned the caravan site into a Passchendaele of mud, the farmer had failed to harvest his silage, and the Maes itself, the site of the Eisteddfod pavilion and other facilities, was a churned up building site, with a quarry of gravel and hardcore having been used to enable the various contractors to set up the event. A few days before the opening however, whichever god shines its light on this small nation, a miracle happened and by the first Saturday the caravans were slowly rolling on to the specially prepared site, and the many dignitaries of local councils, sponsors and organisations were parading their silverware across the Maes.

I always arrive at the Eisteddfod feeling a combination of excitement and dread. It’s a strange meeting of old acquaintances and new friends, of co-operation and competition, of the conservative and radical, the traditional and the avant garde. There are responsibilities to fulfill and opportunities to relax. But by mid-week the old tribal characteristics seem to kick in, and by the end of the week the variety of weird headgear suggested that many on the Maes had gone native.

In recent years many of the most prominent winners in the leading literary and artistic competitions have been inspired by our most primitive stories. Winning the chair at the Meifod eisteddfod in 2003, the poet and musician Twm Morys drew specifically on the image of Heilyn ap Gwyn letting loose all the woes of this world and breaking the spell of Gwales. This year the chair was won by the veteran poet, T. James Jones, who again used references to the pre-Christian world of the Mabinogi and the Celtic deities as a central motif in his awdl or ode in strict metre, on the subject Ffîn or ‘Frontier’. The poem reflects on two particular ‘frontiers’, that between day and night, but also, and more crucially, the frontier between life and death.

Also, interestingly this year, the artist, Iwan Bala, published his collection of essays and images on the theme of Gwales, Hon, an image which has inspired many of his paintings over the years. The book is an inspiring collection of visual images, historical and literary essays, contemporary poetry and prose, as well as a whimsical piece by Jon Gower on the birds of Grassholm.

The collection is a good example of a strand in our culture rarely found on the Eisteddfod field — it combines many different aspects of art and literature to create an unified vision, combining the ancient relevance of Gwales with contemporary interpretations.

All too often at the Eisteddfod the different artistic forms are confined to their own boxed space — literature to the literature tent, music to the main pavilion itself and to various rock and folk venues, dance and theatre to their individual spaces and so on. During recent years, the only main artistic venue on the Maes to have attempted to combine and cross-reference different artistic forms and voices has been the Arts and Crafts pavilion itself, Y Lle Celf, led by the vision of its organising committee, the organiser himself, Robyn Tomos, and leading artists such as Iwan Bala, not forgetting art organisations such as Cywaith Cymru. Usually these cross-over events are based in an installation near the Arts pavilion, and this year featured the work of the artist Sean Harris from mid-Wales who strangely enough again based the piece on the second branch of the Mabinogi. Called Y Pair (The Cauldron) it combined the installation itself with animation, sounds created with original Celtic instruments, as well as poetry and story-telling.

There’s room for the other organising committees, as well as the Eisteddfod itself to break out of their individual disciplines and look at the possibilities of drawing music into the literature tent, or visual art into the theatre. But is this asking too much of the dyed-in-the-wool traditional Eisteddfotwyr?

There has always been a tension between the inherent conservatism of the Eisteddfod establishment and the demands of our multi-media, multi-cultural age. I remember, way back in 1979, taking part in a protest to persuade the Eisteddfod to set-up a rock venue on the field. It was secretly arranged for the leading band of the time, Y Trwynau Coch, to play at the Aberystwyth Welsh Student’s Union tent, causing a furore, and several near-heart attacks in the neighbouring stalls. With time, however, a rock venue was included, at a safe distance from the main pavilion. This year it was good to see several small stages scattered across the field, featuring a wide selection of different musical styles.

Perhaps one of the most dramatic developments in the Eisteddfod’s history was, after decades of temperance, the introduction of a bar on the Maes in the Newport Eisteddfod of 2004. All the ghosts of past fervent Eisteddfodwyr, such as Dewi Emrys, Caradog Pritchard, T. Glynne Davies and many others seemed to congregate there. In Mold the two bars and many excellent bistros and cafés on the Eisteddfod field were the haunt of poets working towards the next ymryson or poetic challenge, or parties and choirs making time before their next performance. This has been an important addition to the ‘Gwales’ experience since its conception. The bars and bistros are open until the main evening concerts. Then the regulars either leave for the concert or theatre, or return to the caravan or camping sites to drink and enjoy their various entertainments.

Before there were bars on the Eisteddfod field at the beginning of the week, scouting parties would be sent out to assess the local pubs and restaurants. And then, gradually over the first days of the week, these haunts would be overwhelmed by the faithful and the famous. Having a bar on the Maes has also changed this relationship with the local community, reinforcing the feel of Gwales as an island apart from the great big world.

During the last decade, the demands of technology, all the various TV channels and broadcasters, the various health and safety regulations, traffic control, and security reponsibilities have forced the Eisteddfod to be very discriminating in its choice of site. This year it was lucky, with the weather and site. But increasingly throughout Wales only a few sites are able to provide the necessary logistical, technical and transport facilities. This precludes many parts of Wales from being able to extend an invitation to the Eisteddfod — most of the south-Wales valleys, Blaenau Ffestiniog, even the Llyn peninsula — many of the places where the Eisteddfod would make a real difference.

No one seems to be seriously looking into an alternative to the all-encompassing Maes, an island, even a ghetto, apart from local towns and communities. Many would argue that the Eisteddfod leaves a lasting impact on the local area. This has still to be proven. Are there alternatives?

Look at a town like Blaenau Ffestiniog. There aren’t many open fields in the area, let alone enough to take the full weight of the Eisteddfod itself, its caravan, camping and parking sites. But I’m sure, in a town like Blaenau Ffestiniog, or Merthyr or Aberdâr, there are plenty of silent chapels, schools on school-holiday, leisure centres, and even abandoned offices or shops which could be recruited to be the arts pavilion, the literature tent, and the many other venues that make up the Eisteddfod field. It would probably be a logistical nightmare, but given the co-operation of the local community, businesses and shops, it could have a lasting impact which the current leviathan doesn’t achieve.

This year’s Eisteddfod was originally invited to Liverpool to be part of the city’s season as the ‘City of Culture’. I would have welcomed that step. The Eisteddfod used to venture to England and even Chicago — to serve the Welsh diaspora at the height of its influence. The opposing voices, based mainly on the drowning of Cwm Celyn in the 1960s to serve the Liverpool Corporation with water, won the day, and the Maes didn’t venture over the Mersey. Ninety years ago, a poet from Trawsfynydd, in the heart of Welsh-speaking Wales, won the chair at the Birkenhead Eisteddfod for his awdl on the Arwr (‘Hero’). His name was Ellis Evans. His pseudonym Hedd Wyn. His name was called. No one rose. The winning poet had been killed during the first hours of the first battle of Passchendaele on 31 July, 1917.

The drowning of Tryweryn was remembered at this year’s Eisteddfod. The death of Hedd Wyn was not. On the stage in 1917, as the name of the winning poet was revealed stood the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and his chief recruiting sargeant, Rev. John Williams of Brynsiencyn, Anglesey. In the days following the chairing of the dead poet, recruitment figures in Wales blossomed.

And yet, in every major gorsedd ceremony, led by the Archdruid, the audience still answers obediently —

‘A oes heddwch?’ — ‘Heddwch!’ (Is there peace? — Peace!)

These contradictions echo down the centuries. During last year’s Eisteddfod near Swansea, the Israeli army and airforce were bombarding southern Lebanon. Israel — its influence to be seen in this year’s winning Christmas Carol in the literature section: ‘I werin dan orchudd y fagddu fe roddwyd/Cipolwg ar lewyrch o Fethlehem dir:’ (‘For a people hidden by darkness was given/A sight of the light of Bethlehem’s land’) — has since the translation of the Bible into Welsh held the Welsh people in a strange armlock. From Bethesda to Nasareth, Nebo to Beulah, the Bible-ridden Welsh have patterned themselves on the chosen nation, turning a blind eye to the horrors that face the citizens of Bethlehem today. Every year the Archdruid has a platform and a presence during the main Eisteddfod events to make a statement about such world events. Very few have taken the opportunity to voice such statements.

There are many contradictions and challenges which face the National Eisteddfod at the beginning of the twenty-first century. In one way it is a huge, media-driven event, filling hours of digitial television space with free material — the payments offered to profesional and amateur competitors and contributors alike are still, despite numerous appeals and protests, peanuts. This year’s event was surprisingly successful, despite the tribulations of water and weather.

Because of the demands of current regulations and technology, and its many sponsors and sustainocrats, the Eisteddfod seems to have no choice, but to continue on its lumbering way towards visiting a few sustainable sites, one in each corner of Wales perhaps. There is another choice, however. To become much more adaptable and sustainable. To perhaps vary from year to year between the current all-encompassing Maes, caravan and camping site to an attempt to use buildings and venues, as well as convenient open-field sites, within smaller towns and communities. To compromise sometimes and not be as prepared to bend to its many media and government masters.

This year’s Eisteddfod at Mold was a great success despite being located in one of the most Anglicised areas of Wales. We still have a huge need for Gwales for one brief week of the year, to lick our wounds, sing our songs and reaffirm the continuing vitality of Welsh-language society and culture. There was a time when the wealth of the Eisteddfod’s literary and cultural output was reported by experienced journalists in the London papers. Today, within the British perspective, we are the disappeared. We have our own language, our own culture, our own history. The Eisteddfod from year to year celebrates that heritage. As the English debate their own identity, and the Prime Minister from Scotland talks about defining ‘Britishness’, very few seem to mention ‘The Island of the Mighty’, or Gwales, or any of the myths and legends indigenous to these islands. In one way I feel that not taking the Eisteddfod to Liverpool was an opportunity missed in opening the eyes of our neighbours and cousins to the wealth and vibrancy of our ancient culture.

It’s not easy to discern straight narrative lines running through the Mabinogi, any more than it’s easy to follow clear definable paths across the Maes. The challenge for the National Eisteddfod is to refuse to slip into easily definable, corporate celebrity-speak, and instead to burrow under the global minefield and reappearing in unexpected places leaving its mark.

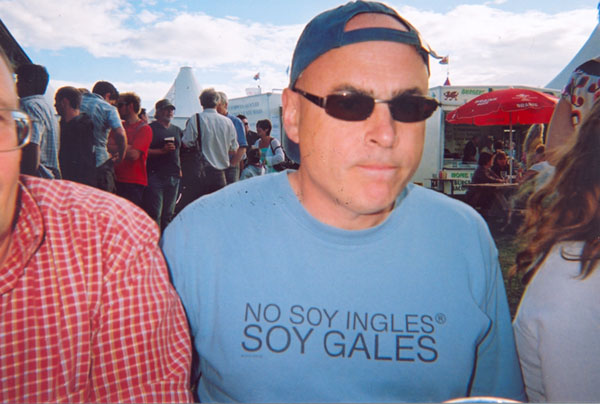

During the last decade the Eisteddfod has withstood many pressures to be more bilingual, transparent and open. In some ways this has been achieved. The translated slogans on many of the stalls are enough to suggest that. But there is no escape from the fact that for the first week in August the tribes of Wales reconvene to face another winter. For a week we live the dream of independence, of a culture free from the shackles of Anglo-Americanism, free to dream of cauldrons and islands and bird-song. Free to create a different perspective.

For a week we keep the door shut. We wallow in the music, the poems, the performances. We turn water into wine at the shrine of the birds of Rhiannon. Before one inquisitive veteran, drunk on Irish cider, decided to open the door.

And then, on Sunday morning, as the rain began spitting again, the caravans began to roll. Out into the big, bad, global world.We feature further reviews and analysis in the magazine. See our contents pages in the archives section and you can buy issues here.

About the author

Iwan Llwyd (1957-2010) is a national treasure.

If you liked this you may also like:

More Eisteddfod

David Rees Davies at the Eisteddfod in 2009

Am dro go iawn

A poet in Patagonia, Iwan Llwyd in Planet 170 - buy it here

Gruff Rhys

In the same issue as this article we have an interview with Gruff Rhys - buy the issue here - planet 185