War Declared! Art and Society in Wales, 1969-77

Planet's winning essay for under 30's from 2010, Huw David Jones looks at Art and Society, a series of exhibitions form 1969-77

Tweet01.10.09

To see a pdf of the article click here

In January 1969, posters went up at railway stations in Cardiff, Swansea and Newport alerting Welsh commuters to a ‘War Scare’. Over the next few weeks more signs appeared on platforms with news of ‘War Crisis Talks’ and ‘War Imminent,’ before finally, on 8 February 1969, it was announced: ‘War Declared!’

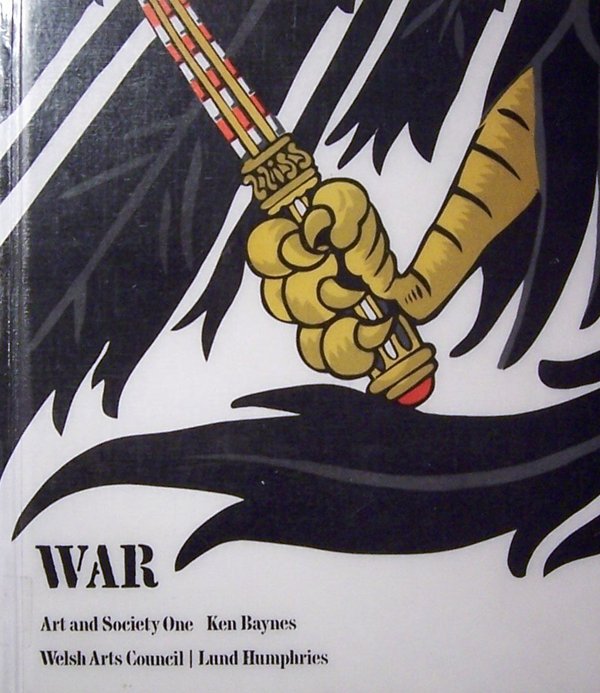

War was the first in a new series of exhibitions called Art and Society, and the Welsh Arts Council’s most ambitious project to date. Opening at Swansea’s Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, it aimed to revolutionise the traditional exhibition format by showing paintings alongside other images, artefacts and sounds associated with the subject of war. Pictures like Graham Sutherland’s scenes of bomb-damaged London appeared next to science fiction comics, photographs of the American civil war or medals and military uniforms from the Imperial War Museum. The normal silence and solemnity of the gallery was shattered by the deafening howl of an air-raid siren or the occasional burst of machine gun fire, while recordings of ‘Yankee Doodle,’ Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, African drums or the electric fuzz of The Beatles’ Revolution played in the background. In one corner of the gallery, there was a child’s board game dating from the Boer War; in another, teenagers huddled over a two-penny slot machine inviting them to ‘fire your own missile’. There was even a Nazi flag, complete with swastika, on display. No attempt was made to distinguish between high art, popular culture and schlock. It was unlike anything seen in a British art gallery before.

The Welsh Arts Council received complaints that its marketing stunt — which also included flying the German Imperial flag from the roof of the National Museum of Wales — was ‘frightening and distasteful’. (Art and Society: War, NLW, WAC Archive, Exhibition Files, A/E/103) Outside the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, a group of anarchists — student politics in Swansea had a strong anarchist element in the late-1960s due to the influence of Ian Bone, later editor of Class War, who studied at the city’s university — staged a protest, saying that the exhibition ‘glorified its subject’. War, however, was a huge box office success, and broke all attendance records at the gallery.

The exhibition was equally well-received when it visited the rest of Wales and the north of England later that year. The press, meanwhile, praised the Welsh Arts Council for attempting such a bold and innovative display. ‘Success is a nebulous term in this context for it is a hackneyed word and cannot adequately suggest the feelings which this exhibition arouses,’ wrote Eric Rowan in The Times (29 Feb, 1969). ‘Perhaps it is possible to become more detached with subsequent visits — which is either a comment on art or on human sensibilities — but the first encounter is undoubtedly a moving experience.’

Art and Society was the brainchild of Gordon Redfern, chief architect of Cwmbran New Town, and a member of the Welsh Arts Council’s Art Committee. The Art Committee had been established in 1965 to give practising artists and designers some say over policy, and quickly established itself as a champion of progressive art in Wales. Redfern, however, thought that some of its more avant-garde exhibitions alienated large sections of the Welsh public. ‘Such exhibitions are considered — often rightly, in my view — by the majority to be esoteric, intellectual and incomprehensible,’ he wrote in a memo to colleagues. ‘This may be an unpleasant truth for us to swallow but it is amply proved by fact and should, I feel, be of great concern to us.’ Redfern wanted to stage a series of ‘popular mobile exhibitions’ looking at how particular social issues — sex, food, money and war were among the suggested titles — had been represented in painting, film, photography, music, fashion and advertising. These would place art in a familiar social setting, and so, Redfern thought, would appeal to more people.

The Art Committee accepted Redfern’s proposal, and asked Peter Jones, its Art Director, to take the project forwards. Since joining the Welsh Arts Council in 1965, Jones had built up a reputation as an open-minded radical and populist, always keen to try out new ideas. More than anyone he was responsible for stimulating the visual arts in Wales in the 1960s and ’70s and raising the nation’s profile on the British and international stage. In 1967, Jones launched a poster print scheme which placed abstract designs on commercial billboards throughout Wales, and a year later he organised the Council’s first ever photography exhibition. Jones was assisted in many of these projects by the designer Ken Baynes, and between them a new policy had begun to emerge which challenged traditional definitions of art and culture.

At the time, most cultural institutions in Britain defined art as painting and sculpture exclusively, and placed a premium on work that conformed to the mainstream development of Western aesthetics. This philosophy stemmed from the Victorian idea that art, along with opera, ballet, literature, theatre and classical music, represented a set of higher moral and spiritual values identified as ‘culture’ — ‘the best that had been thought and said in the world,’ as Matthew Arnold put it — which stood apart from more popular forms of entertainment and pastimes. However, this narrow definition of culture had, since the mid-1950s, come under sustained attack from left-wing academics like Richard Hoggart and Raymond Williams, who exposed its underlying class prejudices. Meanwhile, the exhibition Art and the Industrial Revolution, produced by Marxist art historian Frances Klingender, showed the potential for exploring social themes through art. By the late 1960s, the idea that art and culture were broad concepts reached its radical conclusion in the work of the Canadian critic Marshall McLuhan, who argued that, with the growing influence of television and mass media, culture had expanded to encompass all forms of communication, each as important as the other — a comic book was essentially no different from a painting or sculpture. With Art and Society, Jones and Baynes aimed to turn this theory into reality. As Baynes declared in the War catalogue: ‘A stage has been reached when the Council recognises that the human phenomenon known as art has countless forms, and arises from equally varied impulses.’

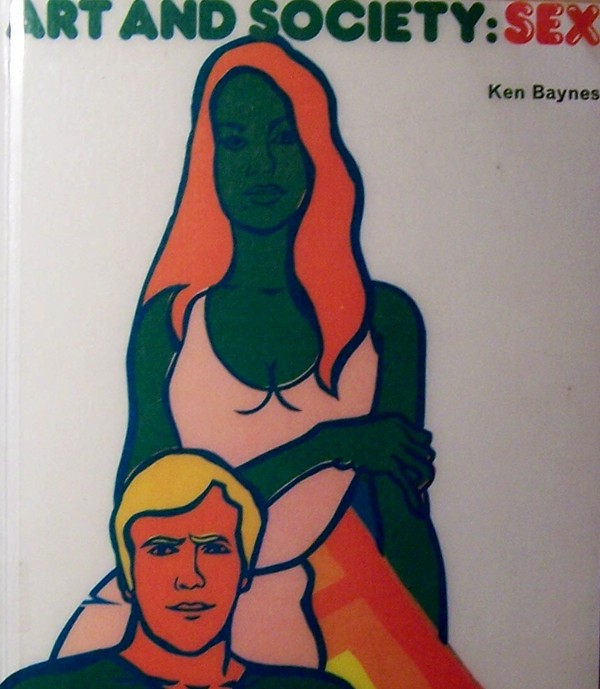

War was followed by three equally successful Art and Society exhibitions on the themes: Work, Worship and Love and Marriage (originally called Sex but changed after complaints from schools and churches). The first of these included a remarkable set of lantern slides produced by the pioneering documentary photographer William Jones showing working conditions in Welsh mines in the early-1900s. It was the only exhibition in the series to include a substantial amount of Welsh material. In an article in Planet (issue 9, 1971), Ken Baynes said he was against the idea that ‘all the Council’s money should be used to promote Welsh art,’ claiming it was contrary to the ‘international milieu in which ‘Welshness’ should operate’. Yet this ambivalence towards Welsh visual culture — a common view on the British Left at the time, and one which perhaps reflected deeper anxieties about the threat posed to traditional class loyalties in Britain by the growth of Welsh nationalism in the late-1960s and early-1970s — was out of step with public mood in Wales: Work proved to be the most popular exhibition of the series, and was seen by 43,484 visitors when it opened at the National Museum of Wales in December 1969.

While Art and Society proved popular with the public, the arts establishment, both in Wales and elsewhere, was quite hostile to the project. Conservatives naturally decried the wilful mixture of popular and high art. But liberals, too, were perturbed by the rejection of traditional standards of taste and judgement. Roger Webster, the former Director of the Welsh Arts Council, professed that, although Art and Society was rooted in the egalitarian tradition of Welsh educationalists like Owen M. Edwards, he had a ‘nagging feeling that we may be fooling ourselves — rather like the contemporary pretence that the Beatles have the same value as Bach.’ (In R. Burnley Jones, ed. Anatomy of Wales, Gweru Publication, 1972). His thoughts were echoed by a senior member of the Council’s Literature Committee, who described the War exhibition in a memo to colleagues as ‘further evidence of the eccentric critical judgement of our colleagues in the visual arts, which I have heard severely censured elsewhere recently.’ Peter Jones, meanwhile, faced criticisms from Gabriel White, his counterpart in the London office of the Arts Council of Great Britain, that the Welsh Arts Council wasn’t dealing in art at all. ‘I took it as something of a reward,’ Jones later joked.

Similar views were also heard when the Welsh Arts Council published a series of illustrated books to accompany Art and Society. One critic described Worship as a ‘book totally ignoring the spiritual aspects of twentieth-century abstract art,’ adding that it was ‘not only parochial but unworthy of being considered even as an introductory essay.’ Another said it was ‘without discrimination between art, kitsch and schlock’. In Scotland, which missed out on the Art and Society tour, the books stimulated a far-reaching debate about whether the Scottish Arts Council should reassess its own idea of art and culture. In February 1971, the radical magazine Scottish International, which carried a series of articles on Art and Society, interviewed the retiring Director of the Scottish Arts Council, Ronald Mavor, and asked him whether Scotland should follow the precedent set by the Work exhibition. ‘I think that as a simple bank the Arts Council is doing a useful job in allowing this to go on,’ he replied. ‘[But] I wouldn’t like to think that either the Marxist position or any other position would have too big a say, in any country, in the way the arts were organised.’

Despite criticisms raised by the arts establishment, the Welsh Arts Council’s Art Committee continued to pursue a policy based on the broad definition of art. Throughout the 1970s, exhibitions were held on such subjects as TV graphics, photography, newspapers, maps, jewellery, toys, masks, fabric and glass. Peter Jones regarded these as amusements. His remarkable influence over the development of the visual arts in Wales shows just how much influence the Council’s specialist officers had at the time, and contradicts the widespread misconception that, because it was made up of the ‘Great and the Good,’ the Council was an inherently conservative organisation. In 1977, Jones organised the Council’s first ever exhibition of performance art at the National Eisteddfod in Wrexham. Featuring 20 presentations by 14 international artists, including world-renowned figures like Joseph Beuys and Mario Mertz, this was its most radical project to date. It was overshadowed, though, by widespread criticism in the press about ‘wasting public money’ on an art-form that few understood, and led to questions in Parliament. At the heart of the dispute was the question of how relevant such exhibitions were to Wales and the Welsh- language culture which the Eisteddfod stood for in particular — a point made in dramatic style by Paul Davies’s Welsh Not, a performance protest against the suppression of the Welsh language, and, although not part of the official programme, the only performance understood by most eisteddfodwyr. This marked the beginning of the end of the Council’s exhibition programme. In 1982, having organised over 200 exhibitions, and under mounting financial pressure, it decided to stop producing its own exhibitions, and concentrate on developing a network of Welsh galleries instead.

Despite its far-reaching influence — the books War, Work, Worship and Sex have been published in six languages, most recently Turkish — Art and Society has so far gone unrecorded in the pages of British cultural history. Even in Welsh art history books it receives scant attention. This is symptomatic of the view, still evident among critics and art historians, that only London exhibitions are historically important. Yet forty years on, the ideas which stimulated Art and Society still have resonance in contemporary debates about culture and cultural policy in particular.

Today, most cultural institutions accept that art and culture are broad concepts, and more support than ever is given to activities like craft, photography, film, performance and community art. Indeed, in Scotland the SNP Government is about to merge the Scottish Arts Council and the film agency Scottish Screen to create a new body called ‘Creative Scotland’. This will not only have responsibility for traditional high arts, but also the wider field of ‘creative industries’, which encompasses things like advertising, comics and video games.

There is much to be celebrated about the use of a broader definition of art and culture. For one, since art can no longer lay claim to a set of higher moral and spiritual values, the old patrician elite have been forced to acknowledge a greater diversity of voices and opinions, including those previously marginalised by gender, ethnicity, sexuality or nationality. Yet this has also led to a kind of relativism in which all forms of culture are seen as equally valid, raising difficult questions about how value judgements are made or why some art objects deserve special privileges like public subsidy.

Many cultural institutions have tried to answer these questions by emphasising the ancillary benefits of the arts. Instead of talking about the intrinsic value of a painting or concert, they now try to demonstrate how culture contributes to wider policy agendas, such as social inclusion, economic regeneration or the improvement of mental health. Yet this has only turned the arts into a tool of government, and eroded the traditional arm’s-length relationship between the artist and the state, which is designed to safeguard artistic freedom. Creative Scotland, for example, has been strongly criticised for subsuming the arts within an economic agenda through its emphasis on the creative industries and their contribution — much of it unsubstantiated — to the Scottish economy.

Art and Society, however, offers a different answer to why we should value and subsidise the arts. Exhibitions like War tried to show that ‘art reflects, interprets and supports man’s concept of himself and the significance of his role in the world.’ In other words, art is important because it helps develop a deeper sense of who we are, where we come from, and what our hopes and aspirations are for the future. This is an essential part of democracy — indeed, it is an essential part of what it means to be human, and the arts should be supported for that reason alone.

We need bodies like the Welsh Arts Council, then, not because they generate jobs, or because they contribute to social policy objectives, but to provide a space in which artists and the public can engage, question and exchange ideas that are relevant to our civic culture in Wales — we need them to develop both our art and our society.

I would like to thank Ken Baynes and Peter Jones for answering my questions about the Art and Society series. References: Richard Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working Class Life (Chatto & Windus, 1957); Raymond Williams, Culture and Society 1780-1950 (Chatto & Windus, 1958); Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man (Penguin, 1964) and The Message is the Medium: An Inventory of Effects (Penguin, 1967)

We feature many further reviews and analysis of cultural performances and events in the magazine also. See our contents pages in the excerpts section and you can buy issues here.