World Film as a Telescope and Microscope 5.03.18

Wales One World Film Festival Director David Gillam

introduces the theme of this year’s festival: Tales from The Silk Road.

Planet is delighted to be collaborating with the 2018 Wales One World Film Festival, and is co-hosting an event on 20th of March at Aberystwyth Arts Centre with one of our authors Sharif Gemie on the history of the Hippie Trail - and his unique angle on this counterflow to the Silk Road - from West to East... www.wowfilmfestival.com/en/events

For 17 years WOW has brought to Wales an eclectic selection of the finest films from across the world. Over the years we’ve shown films from over 60 countries: countries with mature film industries that have produced films of interest throughout that time such as China, Iran, Argentina, Mexico; those that have had a moment in the sun such as Romania when the global cinema industry briefly enthused about a Romanian New Wave (4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days, The Death of Mr Lazerescu), and those that have thrown up the occasional little gem such as Paraguay (Seven Boxes), Laos (The Rocket), Saudi Arabia (Wajda) and Vanuatu (Tanna).

Over the years that I have been choosing the films for WOW I’ve learnt that there are certain themes that prove unfailingly popular. The wide Himalayan landscapes that give a grand sense of armchair travel (The Eagle Hunter’s Son, Travellers & Magicians, Horse Thief, Kekexili: Mountain Patrol), better still if they have a pinch of spirituality too (Paths of the Soul). Stories of children’s lives often prove an effective way of holding a mirror up to the society in which they live (The White Balloon, Lamb).

‘I feel like I make movies because there are things I have to say in order to figure out who I am or my place in the world, or for me to evolve as a person. But until you get to the end of your movie you don’t always realise why you were obsessed with that particular thing.’ Jodie FosterThe Observer 10 December 2017

As a festival director I too am interested in films that help me understand my place in the world. For me film is a tool, like a microscope or a telescope that helps me get to know a little about other people, other places and my relationship with them; the texture of people’s lives ‘over there’.

One of the ‘blank areas’ on the ‘map’ of Western perceptions of the world are the countries of Central Asia. Before this year the only countries on the Silk Road that WOW had regularly showcased were China and Iran. Both were giants of world cinema in the last decades of the 20th century.

When WOW started in 2001, Iranian neo-realism was having a huge influence on filmmakers across the world. Over the last decade Iranian movies seem to have become much less interesting, due to Kiarostami’s decline, the imprisonment of Jafar Panahi (who has been banned from making films for twenty years) and the wider clampdown on artistic expression.

Until now WOW has only shown a handful of films (Angel on the Right, Tulpan, The Light Thief, Turksib) from the five formerly Soviet ‘stans’, or republics of Central Asia – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan – that have such a long and rich history thanks to their central location on the Silk Road.

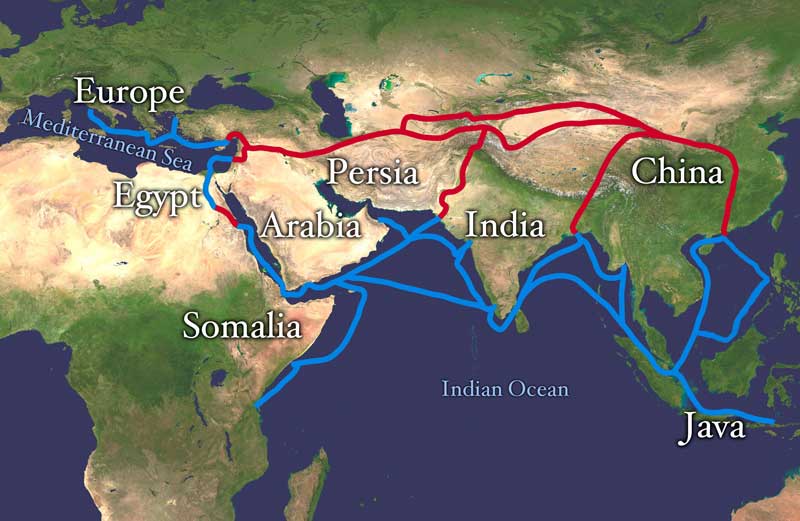

Birgit Beumers, who has co-curated this festival’s ‘Tales from the Silk Road’ programme explains that ‘They from a bridge between West and East, their cultural heritage brings together nomadic with settled cultures, Turkic languages with Farsi, and indeed the corals from the seas transported along trade routes that can be found in the jewellery made of silver abundant in the mountain ranges that cross the region.’

Why the interest in the Silk Road?

For me, international travel is a central thread to a great deal of my movie watching; stimulating my imagination so I can enter other people’s lives in far away places, the heat, the dust, the smell. What is it really like to live there?

Where did this fascination start? A solitary kid’s daydreams about the adventurers who travelled across the world, braving desert storms, mountain passes and all that the wide world could throw at them to reach the fabled destinations of Bokhara, Samarkand, Kashgar and the ultimate Shangri-la, Tibet. The caravan of camels wending its way slowly across the desert wastes under the cruel sun. Lawrence of Arabia – or at least the handsome, heroic Peter O’Toole version.

As an avid reader of travel writing, I was enthralled by Wilfred Thesiger (Arabian Sands), Colin Thubron (To A Mountain in Tibet), William Dalrymple (In Xanadu). This year I read Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. This gives a great sense of the Silk Road not just as a trade route (the china, silk, gunpowder, paper, precious jewels, spices, oil, and myriad wonders) but also the flow back and forth of ideas and religions (Buddhism, Christianity, Islam) and the wonderful mixing of people. Invidious to sum up such a fascinating book that covers so much history and the geopolitics with one quote, but here goes:

‘The struggle for control and influence in these countries produced wars, insurrections and international terrorism – but also opportunities and prospects, not just in Iran, Iraq and Afghanistan, but also in a belt of countries stretching east from the Black Sea, from Syria to Ukraine, Kazakhstan to Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan, and from Russia to China too. The story of the world has always been centred on these countries. But since the time of the invasion of Kuwait, everything has been about the emergence of the New Silk Road.’

(The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, Bloomsbury, 2015)

Extent of Silk Route/Silk Road. Red denotes the land route and the blue is the sea/water route. Image from NASA Visible World, in the public domain.

Why these films?

Each festival programme needs a mix of films – a comedy (always hard to find as humour often doesn’t travel well), a thriller, social realism, family drama, a children’s film, a documentary, some animation. Again the latter can be hard to find though this year we have three: the spectacular fantasy adventure Mary & The Witch’s Flower, the breathtaking Big Fish & Begonia, and the brilliant, biting Have A Nice Day- described by IndieWire as ‘a markedly fresh window into modern China, told with a hypnotic visual style”.

Winner of the World Cinema Special Jury Prize at Sundance Film Festival, Free & Easy is the sort of little gem that WOW specialises in discovering. It’s a wonderful combination of Keaton, Beckett, and Kaurismaki:

‘A frayed Chinese flag flutters listlessly over the tattered fringes of a frostbitten wasteland in the North of the country. So the scene is set for an offbeat, sidelong glance at Chinese society which combines a striking visual impact with underplayed, deadpan humour.’

Wendy Ide’s review on www.screendaily.com

The feature debut of young writer-director Ella Manzheeva, The Gulls is a haunting character study with strong visual appeal. It is set in Kalmykia – the only European nation with Buddhism as the national religion – on the frozen steppes on the edge of the Caspian Sea, where the weather dominates the population’s everyday life. The wind, fog, water, ice and frozen ground also correspond to the lead character Elza’s emotional state.

Although The Gulls deals with the themes of loss and recovery, director Ella Manzheeva sees this film as being one about happiness.

‘We often associate our troubles and the failure with the people around us … However, happiness is within each one of us, and we are the only ones who can let ourselves be happy, daring, free or unhappy. This film is about the energy of life. Slow down. Listen. Listen to yourself and you will hear others. When time finds its space there comes an incredible happiness and freedom, freedom of the soul.’

Mirlan Abdykalykov’s directorial debut Heavenly Nomadic (Sutak) presents an idealised view of nomad life in the high, remote mountains of Kyrgyzstan. It’s the story of the family of the herdsman Akylbek, his wife Karachach, and his daughter-in-law Shaiyr who is the ideal image of a Kyrgyz woman: she is beautiful, she is a good mother, an excellent mistress of the house and a hard worker who treats her father-in-law respectfully and remains loyal to her dead husband.

‘In the behavioural motivation of the protagonists of Heavenly Nomadic lies a strong internal message that emanates from the director’s own character, his outlook and attitude: Mirlan Abdykalykov is very quiet, he speaks little, he is stable and moves slowly to achieve his aims. Abdykalykov is no newcomer to cinema; he has played the lead roles in three films by his father Aktan Abdykalykov (now known as Arym Kubat) who directed The Light Thief (2010).’

Kinokultura, Issue 49, review by Gulbara Tolomushova

With so few slots to fill, the Silk Road season could only be an initial survey of a vast area of cinema. Some places – Tajikistan, Uzbekistan – still remain blank on the map. Not exactly ‘Here Be Dragons’ but with so few films currently being produced in these countries and their quality so ‘variable’ there seemed no point in including a film simply to plant a WOW flag in another country.

I was hugely fortunate to be guided on my journey along the Silk Road by Birgit Beumers, Professor of film studies at the Aberystwyth University, editor of the journals KinoKultura and Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema and world authority on Central Asian cinema who is giving a talk in Aberystwyth on 15 March. https://www.wowfilmfestival.com/en/events

If you appreciated this article, you can read longer articles on a wide range of topics in Planet magazine, and you can buy Planet here.

About the author

David Gillam is Festival Director of the Wales One World Film Festival www.wowfilmfestival.com

If you liked this you may also like:

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…