A Native Alternative 25.06.16

Congratulations to Miriam Elin Jones, the winner of our 2015 Young Writers’ Competition. Frustrated by traditional Welsh-language culture she explores new debates about ‘Welsh futurism’ in music and literature.

by Miriam Elin Jones

Growing up in Wales, I have become accustomed to the fact that we tend to dwell on our past. We grow up singing old hymns and competing in local Eisteddfods performing the infamous ‘ddawns werin’ (folk dance). We seem to be fond of glancing back at a bygone age, when churches and chapels were full, in awe of the slate quarries and picturesque countryside of Kate Roberts’ literature, and we still feature Sydney Curnow Vosper’s Salem as a staple piece of art in the Welsh home. We’re still sulking about Tryweryn, but we’ve forgotten that we saved Llangyndeyrn. As a teenager, of course, this was dreadfully dull and stale. I struggled to enjoy the contemporary Welsh music scene, which consisted of groups of angsty male-driven rock bands or nicey-nice female acoustic singers with sweet voices, exclusively kept for the ‘C2’ programmes aimed at the younger generation. For some reason, they lacked the same hype as their English counterparts, and it was mainly due to the elder generation’s constant tut-tutting and complaints that things aren’t as they were.

A prime example of this was the reaction to Edward H. Dafis, the apparent Welsh super group of the 1970s, and their reunion gig at the Denbigh National Eisteddfod in 2013. The concert prompted furious debate between generations. Thousands flocked to see the band perform for the last time during the National Eisteddfod in Denbigh, bringing the elder generation to mourn the ‘Golden Age’ of Welsh music. Every gig, thereafter, is associated with that pinnacle, and, of course, is labelled shoddy in comparison. Edward H. Dafis remains a daily staple on Radio Cymru and the 2013 gig has been replayed several times on S4C, and has now been released on DVD. Apparently, music is not what it used to be… and this remains our mantra.

How can we even try to compete against the powerful influence of our past? How do we move forward, or should we even consider looking to the future? Dafydd Iwan sings that we’re still here – Yma o Hyd – yet where is the song that informs us that we’re ‘Moving On’? Well done, we’re still here, still celebrating our rich heritage – and that is all well and good – but what next? The 2011 Census shows that the numbers of Welsh speakers are dwindling. Generally, young audiences for Welsh-language concerts and Welsh-language TV programmes are few and far between, but nothing is being done about it. Are we, today’s generation, aware of a place called Neuadd Blaendyff where people used to flock in jam-packed buses to Welsh-language gigs? Probably not. I doubt I’ve even been to a concert in Cardiff’s Motorpoint Arena where people have filled buses to get there. Regardless, what right have we got to judge what the ever-present Elders think?

Recently, I’ve come across a theory that has pushed me to further explore and challenge what I perceived as the Traditional Welsh Identity: an alternative Welsh philosophy based on international music genres and science fiction literature. Rhodri ap Dyfrig’s recently coined term, ‘cymroddyfodoliaeth’ (Welsh futurism, or Celto-futurism) has opened up a new way of thinking about Welsh language culture. (Rhodri ap Dyfrig’s celtofuturism essay, ‘Cymroddyfodoliaeth’ [2014] can be read here.) Based on the Afrofuturism theory – where Black/African diaspora writers, artists and musicians veer towards fantasy and science fiction elements in order to explore a new culture, create new openings for Black peoples, and to revise, and to some extent, rewrite historic events – ap Dyfrig contemplates the role of Welsh science fiction and fantasy, and sees a similar and recurring theme. Musical and visual artists use different media to express an alien alternative to the ‘traditional’ Welsh culture, and by creating an otherworldly distance from that very culture, enable a chance to explore new possibilities.

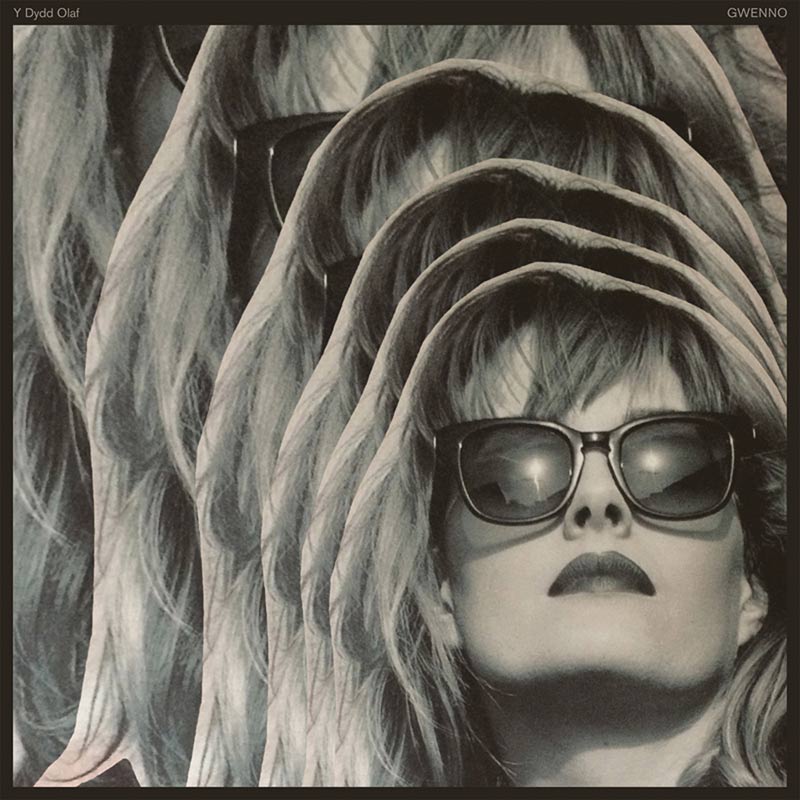

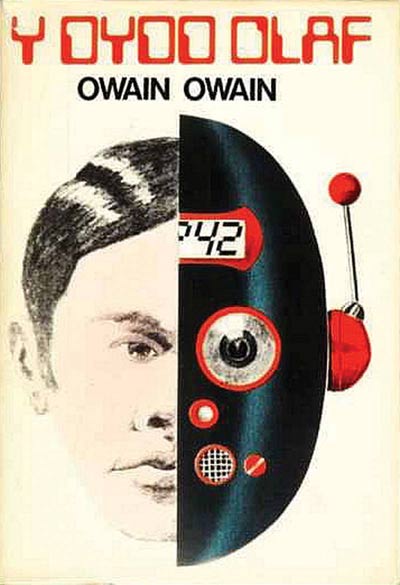

Ap Dyfrig lists musicians, artists, writers and others whose work, it could be argued, align with the concept of ‘cymroddyfodoliaeth’, including Ex-Pippettes singer Gwenno Saunders. To expand on this, Gwenno’s new album, Y Dydd Olaf, takes its title from a Welsh-language science fiction novel of the same name and presents a futuristic and electro-pop sound, a world away from traditional folk music and the protest songs of the 1960s and 1970s that we’re used to. It explores such themes as her personal identity as a Welsh and female musician. The novel the album is named after, Y Dydd Olaf by Owain Owain, is also listed by ap Dyfrig. The book was not well received when published in the 1970s – it was rubbished as ‘complicated’ and ‘too ambitious’ by the judges of the 1970 Prose Medal at the National Eisteddfod – and is merely mentioned (if that) in literary discourse. Yet, it’s a challenging piece of work, praised by Pennar Davies in his introduction to the novel for bringing a new brilliance to the Welsh language literary tradition. Written as a diary, we follow main character Marc’s role in the creation of a dystopian future, where an all-powerful, all-knowing computer called Omega-delta rules, along with a few select members of a ‘Brotherhood’, and turns all civilians into robots. Despite being part of the original plan to create a brotherhood of minority groups, Marc is now swallowed into the new world’s dehumanising regime, writing in Welsh – one of many languages Omega-delta’s numerous programmes don’t understand – in order to protect the contents of his diary. ‘It’s a brilliant novel – a warning, and an embodiment of all the fears that I have about the world; it’s about who is going to control technology in the long-term in particular,’ (as quoted from Amelia Gregory’s interview with Gwenno, published online, Amelia’s Magazine [2014]) explains Gwenno when interviewed, and it’s clear to see that the musician has global issues as well as her own Welsh identity close to her heart.

However, on the whole, whether consciously or subconsciously, it is Gwenno’s feelings towards Wales and Welsh culture that she reveals most strikingly. Science fiction and the alternative element of her music gives her the strength to enable her to do so. Rather than writing under a pseudonym (another way to defamiliarise your culture and begin anew within it) she and similar artists and writers have created a pseudo-world. In the same way as 17th century writer Cyrano de Bergerac uses subtle differences between Earthlings and the men living on the moon to satirise society in his ‘The Other World’ trilogy, artists like Gwenno alienate themselves by creating a distance. By exploring new techniques and experimenting with obscure genres and creating a futuristic setting, she frees herself artistically to express herself honestly. In this sense, Stwff (Stuff) is quite possibly the most revealing track on the album. While discussing this concept, ap Dyfrig quotes:

Pan fydda’i mhell o adre,

mae’r gwir i’w weld yn gliriach,

allai ond ymddiheuro,

am deimlo rhwystredigaeth.

(When I’m far from home,

The truth seems clearer,

I can only apologise

For feeling frustrated.)

Linking this to the Afrofuturism/Celtofuturism theory, it’s easier to make oneself an alien before discussing and criticising the culture one belongs to. Certainly, Gwenno has distanced herself, whether literally in her life or metaphorically through her music, enabling her to be frank regarding her feelings.

In the same track, Gwenno speaks of joining mainstream culture: as well as being well-known as The Pippettes lead singer, she also had a brief stint on Pobol y Cwm and fronted her own programme ‘Ydy Gwenno’n gallu…?’ (Can Gwenno…?) on S4C. She has therefore dabbled with other, arguably more traditional aspects of Welsh culture, before realising suddenly this wasn’t where she belonged and becoming an avant-garde musician, as the following lyrics show:

Yn oriau mân y bore,

Haul yn dangos lan

y llwch ar bopeth.

(In the early hours of the morning,

Sun shows up

all the dust over everything.)

The morning sunshine that fills the room highlights how certain old-fashioned traditions need to be revitalised, like Gwenno’s dust-covered environment. Not only that, but the danger of looking back and remembering a ‘Golden Age’ also appears in the first track of the album, Chwyldro (Revolution):

Twristiaeth

yw teithio ‘nôl mewn amser,

ar dy wyliau,

mewn gwlad dramor.

Ai dyma’r dechrau?

These words remind us that dwelling in the past is merely a form of escapism, compared to going on a foreign holiday. It is a way of burying one’s head in the sand yet again, and refusing to accept the present situation and adapt to its reality.

Despite apparent criticism of stereotypical Welsh culture, Gwenno also upcycles older and more traditional influences. She cites a surprising influence on Golau Arall (Another Light). Having deciphered ‘Golau arall yw tywyllwch/ I arddangos gwir brydferthwch’ (The darkness is another light/ that shows up true beauty) from traditional Welsh hymn, Ar Hyd Y Nos, Gwenno uses the song to celebrate the artist. (As referenced from Aug Stone’s interview with Gwenno, ‘Sense of Emergency: Gwenno interviewed’ The Quietus [2014].) In a similar manner, Guto Dafydd – the recently Crowned bard who’s not afraid to hashtag – wrote in a poem to his brother, ‘I Elis, fy mrawd bach, yn 21’ (To Elis, my younger brother, turning 21);

Paid ag ofni’r tywyllwch; tywyllwch

sy’n gadael iti adnabod

disgleirdeb y sêr.

(Don’t fear the darkness; the darkness

enables you to recognise

the bright stars.)

In a similar way, Dafydd’s poem and Gwenno’s song portray the darkness as an alternative to light, rather than an enemy. For some, the murky void presents inspiration of a different kind. The night-time void is that thing that we know nothing about, the dark underworld community that nurtures an alternative culture.

Returning to Golau Arall, Gwenno asks the artists she celebrates where their path will take them, and encourages them to go further afield.

Lle ei di i grwydro?

Gad dy fyd.

(Where will you wander?

Leave your world.)

The ‘Gad dy fyd’ encourages others to venture further afield: leaving your own culture and exploring other worlds gives you the freedom to express your thoughts, giving you something new to say.

Indeed, the other-worldly and futuristic feel of Y Dydd Olaf makes it a far cry from what we’re used to. However, it came as a surprise to me to learn that Celtofuturism isn’t exactly a new thing. In his essay, ap Dyfrig also lists Llwybr Llaethog, a Welsh-language dub band which have been composing and performing since the 1980s, and have released twelve albums in total. Llwybr Llaethog is a translation of ‘the Milky Way’, and the duo have been lurking on the outskirts of the Welsh language music scene for decades. Welsh science fiction literature isn’t new either – poet Ceiriog wrote fictional letters from character Syr Meurig Grynswth from the moon in the 1860s, and was a contemporary to the ‘Father of the Welsh Novel’ Daniel Owen. These letters vented the constant scorn of Syr Meurig as he studied the world from a large telescope, naming and shaming the sinners he saw below him on Earth. Later, Islwyn Ffowc Elis continued with the tradition by publishing Wythnos yng Nghymru Fydd (A Week in Future Wales) in 1957 and Y Blaned Dirion (The Meek Planet) in 1968. An artist or writer alienating him or herself in order to criticise is certainly not a new concept, even if Celtofuturism, as a term, is. However, it is ironic that in contemporary mainstream culture we take great pride in the fact BBC Wales produces and films Doctor Who, yet the Welsh love affair with sci-fi ends there, with such literature falling by the wayside and no sign of S4/C commissioning a similar series. It remains an alternative.

Returning to the introduction, I’m suddenly aware my sweeping statements need to be revised… There is an alternative Welsh culture, we’ve just proven that. There is more to Wales than rolling countryside and watching rugby. Using street sounds recorded on her mobile phone to create the beat and rhythm to her tracks, Gwenno portrays a Wales and a common cultural anxiety that I can relate to, as a Welsh-speaker in my early twenties. The first track of the album, as we’ve mentioned, brings to mind Saunders Lewis’ famous ‘Tynged yr Iaith’ (Fate of the Language) speech, as Gwenno sings, ‘Paid anghofio fod dy galon yn y chwyldro.’ (Don’t forget your heart is in the revolution.) Y Dydd Olaf is part of Gwenno’s revolution, and the ‘native’ is at the heart of her alternative.

Somehow, a compromise, a new creation is a must – not a backwards glance at the past or a total relocation to the future – but something that is relevant to our present. There is a distinct lack of Welsh-language programmes for the teenage and twenty-something age group, and the scorn shown towards what is published or broadcast for the younger generation is damaging. We shouldn’t be scared to admit our chapels are empty, nor should we be embarrassed to embrace the Eisteddfod’s ‘dawnsio disco’ (disco dancing) competition. If we believe Darwin’s survival of the fittest theory, our Welsh-language culture needs to evolve, and form a hybrid of traditional elements and the likes of Gwenno’s style of futuristic exploration in order to represent the lives we live today.

About the author

Miriam Elin Jones is currently completing a PhD in Welsh-language science fiction at Aberystwyth University

If you liked this you may also like:

Searching for Dic Aberdaron

Bill Rees scoured the margins of land and sea in pursuit of the enigmatic Welsh scholar, linguist and tramp, Dic Aberdaron

Pride: review

Mike Parker reviews the film Pride. Set in 1984 during the Miner's Strike, the London Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners group joins the strikers of Dulais; you are challenged no to be moved.

The Poet, The Donkey and the Quandary

Sion Tomos Owen describes how his passion for politics was shaped by the course of the global recession and his experience of unemployment.

Our readers respond to half a century of Planet!

This year, as the pandemic necessitated Planet’s 50th birthday party to be postponed until regulations are lifted, we invited our readers to send in their stories and anecdotes about the magazine. We thank everyone who replied for sharing their thoughts, and hope to welcome readers near and far to a celebratory event before too long…