Mapping Welsh Identity through Photography

A Conversation with David Hurn, Amanda Jackson, Brian David Stevens,

Huw Alden Davies and Ellie Hopkins 24.06.20

Luisa De la Concha Montes interviews photographers from Wales about how the medium has developed across generations. Does David Hurn’s ‘spiderweb’ tool for understanding locality resonate today? And is there a common thread between the work of those photographers who came of age in the 1960s and those who are emerging now?

Creative responses by students from the School of English, Communication and Philosophy (ENCAP) at Cardiff University, commissioned and published as part of our sponsorship partnership with ENCAP.

On February 15th, 2020, eighty-five year-old photographer David Hurn delivered a lecture at Cardiff University’s School of Journalism, Media and Culture. This was a special occasion as he saw this as the final lecture he would make. The conference was extremely educational, and David’s perspective, always humble and honest, was truly refreshing. However, the evening was tinged with a sense of nostalgia. As David Hurn described how he landed an assistant position with Bruce Davidson at the beginning of his career, or how he casually ran into Sergio Larrain in Trafalgar Square, I realised that the world of the sixties, permeated by a sense of accidental accessibility where photographers could stumble into creative success by being in the right place at the right time, no longer exists. I left the conference with more questions than answers. How do I use this knowledge to navigate the current world of photography? Is it still possible to find a common thread between photographers then and photographers now?

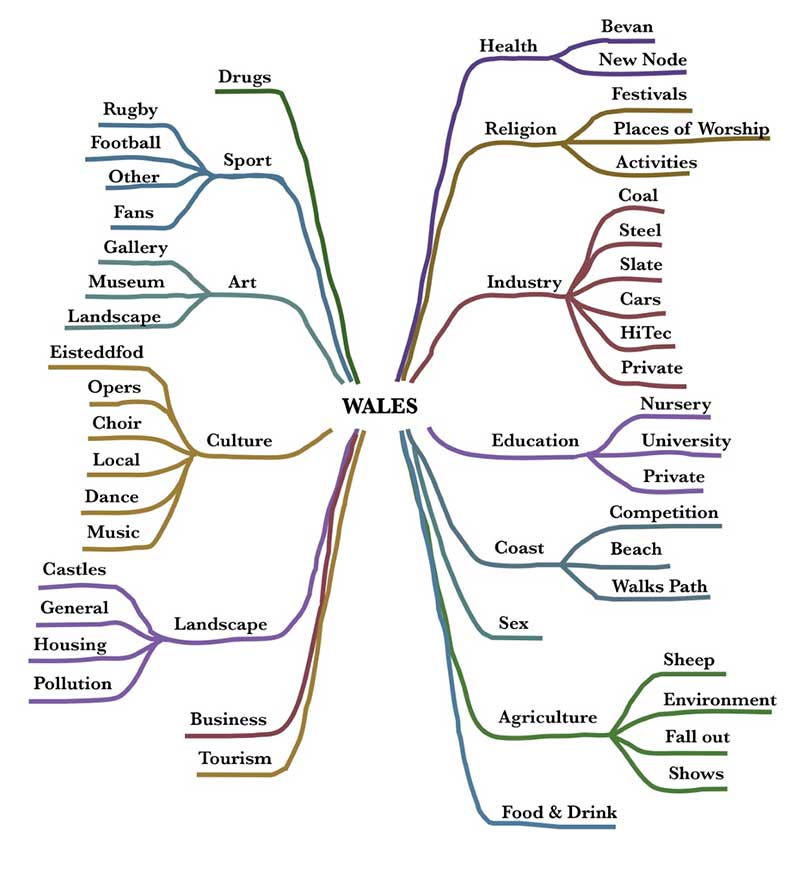

A month later, still wishing to find an answer to my questions, I called David, and our conversation led us to talk about one of the slides he had presented during the conference: a spiderweb map of Wales. When I first saw this map, it brought back many conversations I had had about Wales with my Mexican family: ‘Yes, it is in Britain. No, it isn’t England. Yes, it is in the United Kingdom. No, it’s not a county, Wales is a country of its own.’ Wales is a complex, confusing, and ambiguous landscape. Understandably, I was quite shocked when I saw David’s spiderweb: his representation of Wales was quite clear; he had managed to encapsulate Wales into distinct concepts and categories.

David Hurn’s ‘spiderweb’ map of Wales.

He explained that these spiderwebs are a ‘visual crutch’, a strategic tool he uses to define his projects: ‘In photography, location is key, it helps you frame the narrative of the story.’ Through the use of spiderwebs, he defines the main themes of his projects, such as the essence, the action, and the elements that personally attract him to a certain place. As he explained this, I realised that this spiderweb concept could help me bridge the gaps between his generation and mine. Moreover, it could be used as a tool to develop a better visual understanding of Wales through contemporary photography. With these ideas in mind, I interviewed three photographers: Amanda Jackson, Brian David Stevens and Huw Alden Davies. Along the way, I found out that Ellie Hopkins is doing her PhD on Welsh photography and identity, so I also interviewed her to find more about her thoughts on this.

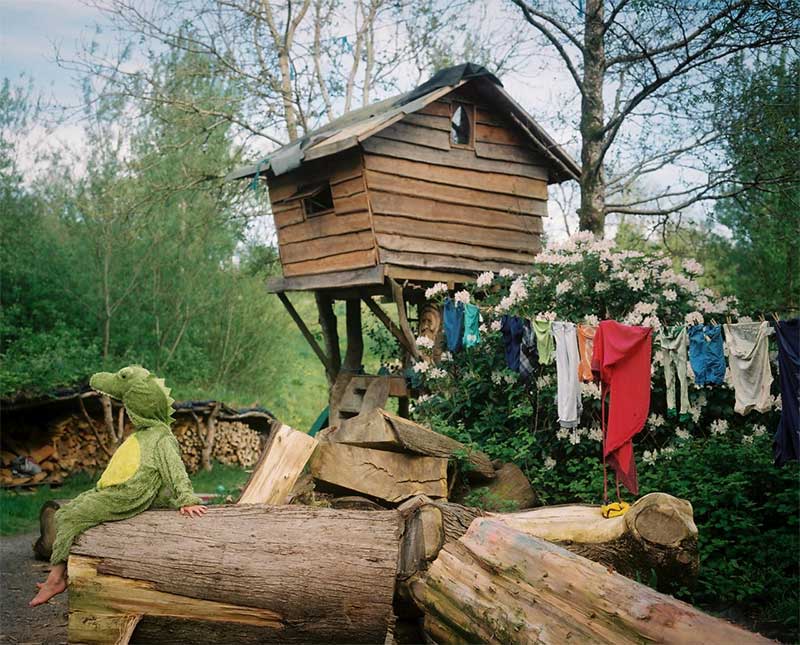

Amanda Jackson was the first person I interviewed. Her project, ‘To Build A Home’, is a documentary project based in Lammas Eco Village, a sustainable community near Crymych in Pembrokeshire. Her project is tangible and immersive; the evocative and recurrent accentuation of green hues and the honest portrayal of the Lammas community made me feel as if I was actually there. Through my conversation with Amanda, I realised that the immersive nature of the project was achieved through two main factors, one practical and one emotional. The practical side had to do with the type of film that she used: Fujifilm Pro 160 or 400, which gives the images a ‘green’ tone to them. The emotional side, however, is a bit more complex. Between 2011 and 2013, Amanda actually moved to a caravan in the village to live there. She still owns a piece of land and goes back to Lammas at least once a year. Because of this, her project is not about documenting a community that is foreign to her; quite the opposite, this community has become part of her own identity.

She acknowledges that initially, she was uncertain about incorporating her personal life into her photography project: ‘In the series, there is a picture of my compost toilet. Originally, I didn’t know if I wanted to include my land, but then I decided I would, because it is all part of it.’ Her own knowledge and experience of living in Lammas feeds into each image, portraying both the idyllic natural landscape, and the harsh reality of it – surviving the winter, and learning to earn 75% of their needs off the land. Moreover, her subjects do not fall into the romanticism of conventional documentary photography; they don’t look gloomy or distant, which is done intentionally: ‘I think that approach can be fashionable, but I like vibrancy. I don’t like to force people to look all downbeat or tired.’ These little clues reveal the dedication and respect that Amanda has for Lammas. Looking at Amanda’s photos is a privilege because it feels like a friendly invitation to visit the community. I know I’m not just looking at some people living somewhere, I am looking at a real community, with all the complexities of living in a sustainable home in the twenty-first century.

Cân Yr Adar, 2013. Amanda Jackson, ‘To Build A Home’.

Crocodile of Pembrokeshire, 2013. Amanda Jackson, ‘To Build A Home’.

Originally, I was a little worried about the fact that I was writing an article about Welsh photography, but that some of the photographers, like Amanda, were not Welsh. Was I contradicting myself? I asked Ellie Hopkins whether she thought it was problematic to try to represent a country when you are not strictly part of it. She replied: ‘Photography shouldn’t always be inward-looking, it shouldn’t always have people who identify themselves as being of that nation. We need “dynamic” photography communities.’ This made me realise that my own biases about what constitutes national belonging had fed into an erroneous outlook: Amanda’s background did not affect the honesty or authority of her project. In fact, photography can work as an effective opposition against the nationalistic and often divisive speeches that dominate our media. After all, Ellie explains, ‘photography is like a language, and in the same way that there are lots of Welsh accents, there are lots of ways of constructing Wales through photography.’ Photography can therefore help improve the understanding we have of our own identity; it is a medium that can allow us to borrow external views and perspectives to then use them to understand who we really are. In line with this, Amanda told me that a key figure in the development of her project was one of her teachers from college: ‘The way he saw my photographs completely changed how I saw the story.’ This made me realise that photography can exist beyond the author in the same way a nation can exist beyond the individual. Moreover, different ways of seeing can lead to different photographic experiences.

This contrast between the personal and the national was further emphasised when I talked to Brian David Stevens about his ‘Beachy Head’ project. I have never been to Beachy Head in East Sussex, but I am familiar with the complex connotations this landscape has. ‘It’s a complicated landscape, full of juxtapositions. It’s a famous suicide spot, but it’s also the biggest cliffs in England and part of the Severn Sisters.’ Before interviewing Brian, I was aware that his project is not based in Wales, but I felt naturally drawn to it. I wanted to explore Brian’s own creative process as a photographer with a Welsh heritage, and to understand the significance of such an iconic British landscape.

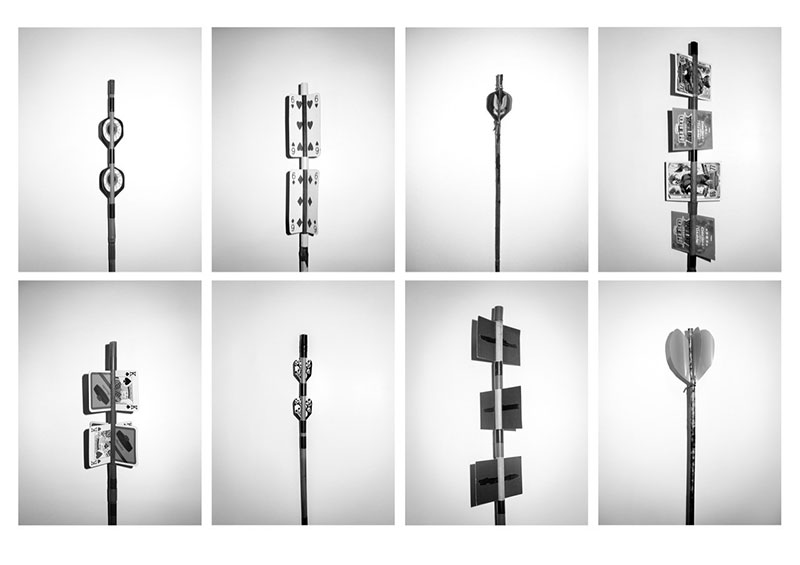

Brian spent a whole year venturing between his home in London and Beachy Head: ‘I would get the first train from Victoria, which is around 5am, and then I’d get a taxi from Eastbourne to Beachy Head.’ He told me how he slowly got acquainted with the systems surrounding this landscape: taxi drivers have a code they can enter into the radio, which will indicate that they got someone in the cab going to Beachy Head who they might be concerned about. Additionally, there is a Head Chaplaincy with volunteers who talk to people on the cliff, often saving their lives. There are also two phone booths with direct lines to the Samaritans. Brian decided to develop his project around the two-mile area between these two phone boxes. In a similar way to David’s spiderweb, these elements helped him define the project’s essence: ‘This place is often where people make their last phone calls home, so I felt that structurally, they were important for the story.’

Beachy Head phone box and Samaritan’s information. Brian David Stevens, ‘Beachy Head.’

Brian’s approach to the project was almost formulaic: ‘It was like gathering evidence, of people being there, and of the traces they left on the landscape’. However, this does not mean that the project is detached from subjective readings: the emotional strength of each photograph is undeniable. His project is permeated by a strong sense of solitude, silence, and grief. For instance, the image Crows is strangely similar to Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows – which incidentally, was Van Gogh’s last painting. The landscape feels ‘conclusive’; the contrast between the cliffs, the water, and the sky feels like the end of the world, or like a modern age biblical scenario.

Crows. Brian David Stevens, ‘Beachy Head’.

There are also photographs of objects: an abandoned backpack, an unused ‘return’ train ticket, flower bouquets and crosses. There is even a desire path leading to the edge of the cliff. These elements make the project feel open ended: ‘These objects could have just been dropped or left behind, but when you see them in the context of finding them on Beachy Head, they become something different.’ It’s almost impossible to escape the connotations that the landscape makes of the objects: ‘You can’t get around the suicide side of it, nor should you.’

Roses left at the top of the cliff. Brian David Stevens, ‘Beachy Head’.

In the same way as suicide inevitably permeates the identity of Beachy Head, I started wondering if there were any elements that permeate the identity of Wales. Huw Alden Davis, who is currently working on his latest project ‘Xennial’ argued that indeed, some elements of Welsh culture are inevitably British: ‘We all hold on to these little traits that we feel as ours, like the Welsh dragon, the leek, or the daffodil, but beyond these little things, beyond the song and the poetry, what else can exist? Who are we?’ Is it possible to create a Welsh identity that goes beyond the stereotypes? Ellie Hopkins argues that it all depends on who and how stereotypes are used: ‘Stereotypes can help people to maintain their national identity’, but they can also be harmfully used to misrepresent a whole nation. As an example of this, she mentioned the 2013 BBC article, The Unbearable Sadness of the Welsh Valleys. However, Ellie has also found that stereotypes can often be cathartic: wrongful portrayals of Wales have mobilised native photographers to counteract these depictions by creating their own. An example of this is the project ‘Ffasiwn’ by Clémentine Schneiderman, a collaboration with stylist Charlotte James from Merthyr Tydfil, which portrays Welsh children in the Valleys wearing complex couture attires. Ellie argues that the wonderful accomplishment of this project is that ‘the stereotype lives in the background and gives a way of context, but isn’t all about it’. Similarly, Dan Wood’s project ‘Suicide Machine’ was born from his desire to talk about Bridgend beyond its tabloid representation as a ‘suicide town’.

Huw Alden Davis’ ‘Xennial’ project is also a response to contemporary Wales. ‘Xennial’ is the name of those born between Generation X and the Millennial generation. For Huw, this generation is the original multi-media generation, which is why he has decided to bring it to life through the use of various digital forms – such as video, live-streaming, audio and writing. The project is partly about technological determinism, but it’s also about nostalgia and Welsh identity. Through a mishmash of digital paraphernalia, and concepts inspired by thinkers such as Canadian media philosopher Marshall McLuhan, Huw does not limit himself in terms of form (why would he? The medium is the message, after all, as McLuhan argued). However, he acknowledges that this means of execution has made it difficult for him to engage with older generations: ‘They question my motives. They don’t understand what this project is about. They tell me, “why are you doing this over here? Is that the project? I don’t know what I’m meant to be looking at”’. Contrastingly, he acknowledges that people from his generation and younger generations have no difficulty in understanding his project. This reflection leads me to draw a correlation between Huw’s project and Wales: The landscape of contemporary Wales, like the landscape of ‘Xennial’ is not singular; it lives through and is transformed by different formats, it’s indefinable, complex and often ambiguous. And more often than not, older generations are struggling to understand it.

Xennial: Dreaming in Colour. Huw Alden Davis, ‘Xennial’.

Xennial: Dreaming in Colour. Huw Alden Davis, ‘Xennial’.

However, despite generational differences, I conclude by realising that the generational gaps between David Hurn’s world and mine are purely symbolic. Regardless of the technological, cultural and social changes that the photography world has undergone since the 1960s, after exploring the fertile ground of contemporary Welsh photography, I realise that what motivated David – the desire to create a true and discernible identity through photography – is still tangible in the work of all the practitioners I interviewed. This makes me hopeful, as I see the future of photography as a way of mapping identity, and as a form of questioning and redefining national bonds. But more than anything else, I see photography as a way of turning the ambiguous idea of ‘place’ into a form of active human inquiry.

-

Notes:

If you are affected by the themes of suicide discussed in this article you can call the Samaritans for free on 116 123.

Amanda Jackson’s website and Instagram account:

http://www.amandajaxn.co.uk/

https://www.instagram.com/amandajaxnphoto/

Brian David Stevens’ website and Instagram account:

https://briandavidstevens.com/

https://www.instagram.com/bds1970/

Huw Alden Davies’ website and Instagram account:

https://www.huwdaviesphotography.com/

https://www.instagram.com/huwaldendavies/

Ellie Hopkins’ website and Instagram account:

http://elliehopkinsphoto.com/

https://www.instagram.com/ell.iehopkins/

The article was amended on 29.06.20 to correct the reference from 'Severn systems' to 'Severn Sisters'.

About the author

Luisa De la Concha Montes is a third-year English Literature and Journalism student at Cardiff University. Instagram: @erst.while Twitter: @L_D_C_M ]

Further articles from Planet Platform:

Faith Clarke

‘I’m not lazy like those people’: How austerity rations our compassion

Greg Taylor

Reflections on 'Welsh Keywords'

Bethany E. Williams

Flora and Fauna

Natalie Cox

Retracing Wales | Discover the Shape of a Nation