‘I’m not lazy like those people’: How austerity rations our compassion 16.08.19

Creative responses by masters students from the School of Journalism, Media and Culture (JOMEC) at Cardiff University, commissioned and published as part of our sponsorship partnership with JOMEC.

Faith Clarke draws on her experiences of interviewing people in Cardiff for a film project on women and austerity to argue that cuts to government spending mark a profound shift away from solidarity and towards a callous re-definition of ‘fairness’.

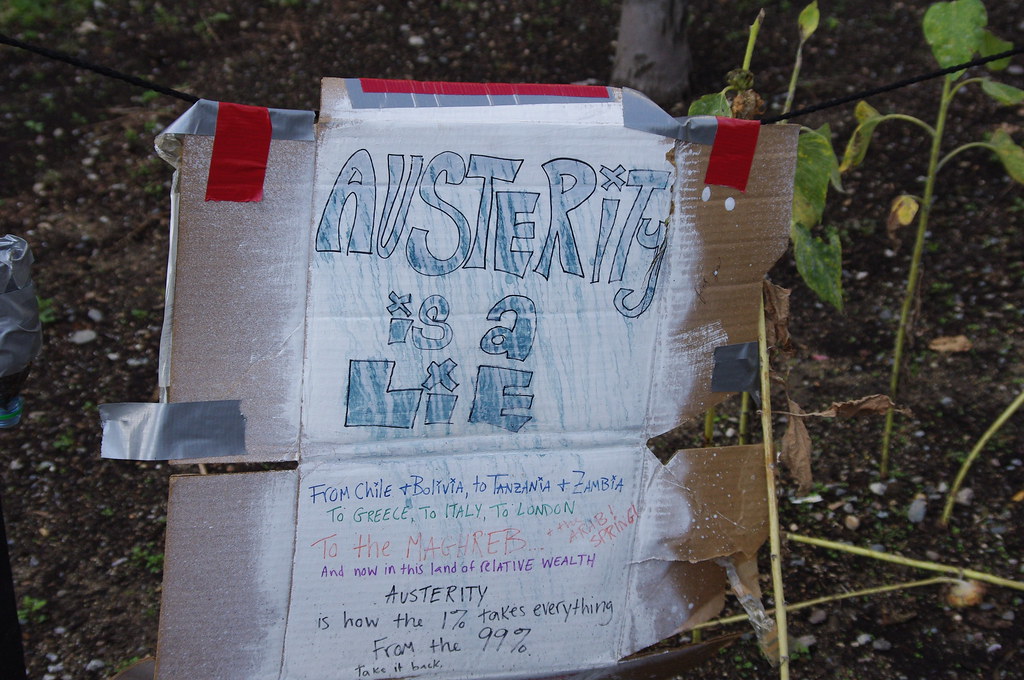

Austerity is a word that crept into our vocabulary around 2010, when a Conservative and Lib Dem coalition took force at Westminster. We saw austerity in motion with the capping, cutting and freezing of many welfare benefits, affecting child benefits, housing allowances, disability benefits, maternity grants, and pensions - to name just a few.

While the word was absent from speeches of its perpetrators (George Osborne comes to mind), austerity as a term frequented the speeches of the Opposition, who saw the cuts as an attempt to make the poor poorer, and rich richer.

Yet austerity is a word we hear so frequently now that it seems to have lost its meaning. Perhaps this is because austerity has become an everyday ‘thing’ that affects so many aspects of our lives: elderly relatives aren’t receiving the care they need, and local leisure centres, youth hubs and libraries are closing. Foodbank donation boxes are normal; tents on the high street commonplace. Child poverty in the Valleys - stories of children without shoes - have stopped shocking people.

However, for some, including those most affected by it, ‘austerity’ is unfamiliar as a concept.

A few weeks back, filming on Queen Street in Cardiff, a woman who approached me for spare change asked me what I was filming.

‘A documentary about women and austerity,’ I replied, feeling slightly awkward.

‘What’s that?’ she asked.

Perhaps that was the goal all along: to keep people in the dark.

All I could reply was: ‘Cuts. Government cuts.’

Simply put, austerity is the slashing of government spending, with welfare usually taking the brunt of cuts. One interviewee likened it to rationing during war periods, and I guess in many ways it’s true. The major difference is however, that wartime rationing was based upon egalitarian principles, whereas under austerity, inequality has only increased.

Furthermore, a deeper, more psychological reading of austerity unveils it as not just a set of harsh, right-leaning policies, but a whole way of thinking. It’s a project that Dr Andy Williams, a lecturer in Human Geography at Cardiff University, describes as ‘inherently ideological’.

During my interview with Andy, we cast our minds back to 2010, when David Cameron, newly elected as prime minister, reinvented the meaning of our welfare state; he suggested that fairness means giving people ‘what they deserve’. ‘[Austerity] is a model project in terms of getting people to think about poverty differently,’ explains Andy. ‘What we’ve seen in the last ten years is this hardening of mentalities towards people suffering.’

This notion of ‘fairness’ - of getting what you deserve - is embodied within the controversial Universal Credit system, where so many claimants are continually pressured into searching for work - and proving it.

We have all heard the horror stories of Universal Credit. Long waiting times are driving claimants to foodbanks, and many have seen their old benefits reduced significantly. The austere (i.e. heartless ) attitudes of many tasked with supervising and micro-managing the job searches of claimants has been deemed necessary to meet the targets of getting more people into work and fewer on benefits. Andy made the point that for many suffering from in-work poverty and poor labour conditions, resentment breeds easily, causing bitterness towards those who are out of work but claiming more money than some in work.

Sanctioning under Universal Credit is a massive issue, with an increase from 0.3% of Job Seekers’ Allowance claimants being sanctioned to 8.2% of Universal Credit claimants. What is clear with the reform is that there is a prominent desire to ‘punish’. That if you don’t turn up - whether you can’t be bothered or whether the letter giving details of your appointment didn’t arrive in the post - you will suffer.

What’s worse though is that this perverse notion of ‘fairness’ has seeped into many of our mindsets. It’s fuelled our perceptions of what people deserve. It’s evident in the debate surrounding the increased number of homeless people on our streets - ‘why aren’t they sleeping in a hostel?’, ‘Are they spending my change on drugs?’, ‘Well, they’re wearing a pair of Nike trainers’. ‘If they’re an asylum seeker, where did they get a mobile phone?’, or, ‘how are there so many nice cars on the council estate?’

Ironically, while smartphones are seen as ‘luxuries’, the state expects benefits claimants to be digitally literate, with Universal Credit applications and job searches filled in and monitored online. I, Daniel Blake comes to mind - when he’s trying to fill in his application at a local library but has never used a computer before.

‘There’s an increased pressure for people to prove that they’re digitally literate,’ notes Andy. ‘If they don’t have a mobile phone, they can’t have their benefits - because it’s all online these days. So access to a computer, access to a phone, is an essential good, not a luxury.’

Austerity is not just the rationing of resources but the rationing of our emotional response to others. We’re all guilty of it to some extent. It’s turned social groups against each other. The homeless blame the refugees, and not only the middle classes - but also the working poor - blame the benefit ‘scroungers’.

‘Compassion itself hasn’t hardened, but it’s being increasingly rationed,’ suggests Andy. ‘What we’ve seen is an increased stigmatisation of people who, for whatever reason, are seen as undeserving.’

When I mention Universal Credit to one woman in Cardiff, Anna (not her real name), who has been homeless on and off throughout her teens and has lived in a hostel for the past year and a half, sneers and shrugs: ‘I’m not lazy like those people.’

While Anna is encouraging passers-by to sign her petition for more social housing, I bring up sanctioning, and tell her the experience I heard of one woman with three kids who was sanctioned for turning up late to an appointment after her bus didn’t show up.

Anna and I debate this for a couple of minutes. Every time I suggest a barrier or obstacle, she finds a way to get around it.

‘Leave earlier - like they tell us,’ Anna suggests.

‘What if you already are leaving earlier?’ I ask.

‘Walk? I’ve had to walk from St Mellons to the job centre. That’s eight miles. If it’s gotta be done, it’s gotta be done. It’s as simple as that.’

‘Didn’t she think it was a bit unfair?’, I ask. ‘Was it necessary to be so harsh?’

‘Not on everybody, but on some people who are lazy, maybe?’ Anna suggests.

It hit home then: austerity had succeeded at least in segregating people who should share a mutual sense of anger and injustice towards the government. It was turning people against each other.

Andy suggests that austerity sees a shift from collectivism, which the welfare state was founded upon, to individualism, which breeds an ‘every-man-for-himself’ sentiment.

Yet some people I interview disagree. Interestingly, a woman I come across selling The Big Issue in Cardiff, Louise (not her real name), suggests that people need to take ‘some responsibility.’

Louise was homeless for four years but was recently housed in what she describes as ‘a very nice flat’. Relying on ESA payment and selling The Big Issue, she still struggles to make ends meet, attending a breakfast club twice a week.

‘People say “government, government”… and I certainly don’t praise this government, but I think it’s also necessary for people to take back some kind of responsibility,’ says Louise, lighting up her cigarette. She gestures at the designer stores lining the streets of The Hayes in the city centre.

‘We as individuals have to ask ourselves about our own lifestyle, how much money we have, how much money we spend… we’re surrounded by shops and people shopping for useless things.’

What Louise refers to seems a bigger question of capitalism, which, in a broad sense, accounts for the widening gap between the rich and poor in the UK - the difference between the shoppers in the Hayes and herself. Yet still, it begs the question of who holds the blame for greed and rampant consumerism. It’s a chicken-and-egg scenario. The consumer supplies the demand, but the supplier creates that want - that need - in the first place.

What is clear is that the government have managed to make people question what ‘fairness’ means, who deserves a helping hand, and who doesn’t. There’s been a shift from collectivism to individualism; the individual has become responsible for his/her circumstances, disregarding the important fact that, for those who haven’t inherited capital and social status, their resources have been desperately reduced or snatched away altogether, leaving them dispossessed.

‘Increasingly we see welfare through this particular lens of deservedness,’ Andy points out. ‘I have no right to judge who’s deserving and who’s not deserving - humanity makes no distinction between the perpetrator or the victim or the hero. We’re all three. All of us - we’re quite messy.’

Short clip of Andy Williams from Cardiff University School of Geography and Planning, defining austerity in an interview in May 2019. Video © Faith Clarke.

About the author

Faith Clarke is an MA International Journalism student at JOMEC in Cardiff University.

Further articles from Planet Platform:

Maria Aguado

Slow-cooking Memories of Home

Songtao Lin

Discover Wales through international eyes

Natalie Cox

Retracing Wales: Discover the Shape of a Nation

Yupei Wang

Wales and Ankang: What to Do About Their Language Decline?